Introduction: Grammar as the Mirror of Meaning

Arabic grammar is not a cold skeleton of rigid rules, nor a scholastic luxury reserved for specialists. It is the compass by which the reader navigates the ocean of divine speech. When grammatical inflection shifts, meaning bends—and sometimes breaks. A single vowel may redirect theology; a single syntactic relation may tilt doctrine.

Here, skepticism is not rebellion but reverence. Can divine intent truly be grasped through intuition alone? Or does the Qur’an—precise, measured, miraculous—demand precise tools? This article argues that grammar is not an optional embellishment, but a methodological necessity for understanding the speech of God.

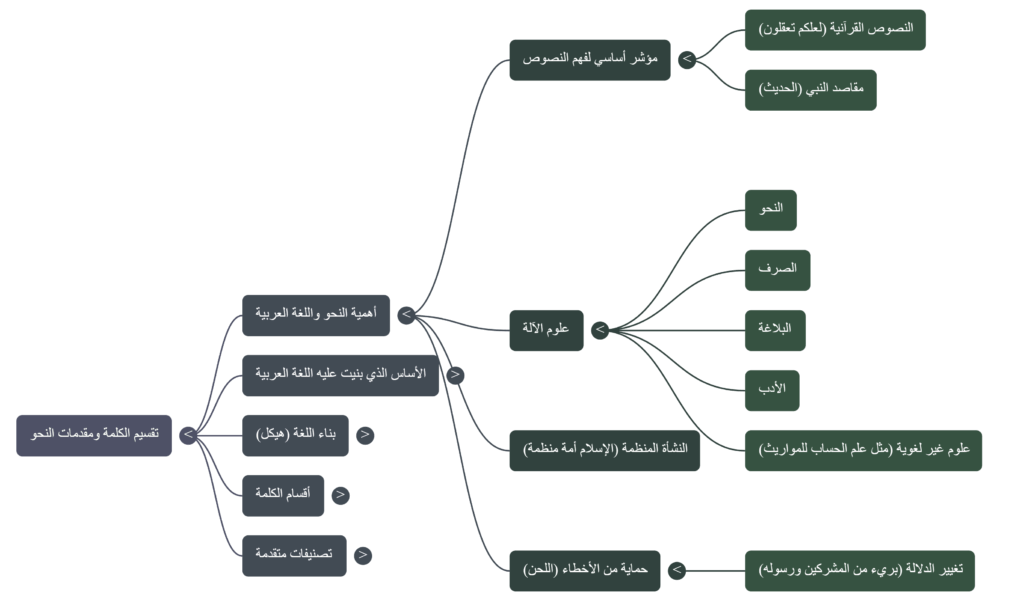

1. Why Grammar Matters: Grammar as an Instrumental Science

Arabic grammar (naḥw), alongside morphology (ṣarf) and rhetoric (balāghah), belongs to what classical scholars termed “ʿUlūm al-Ālah”—instrumental sciences. These are disciplines not pursued for their own sake, but because other sciences cannot stand without them. Just as arithmetic serves inheritance law, grammar serves Qur’anic interpretation.

Exegetes, jurists, and theologians rely on grammatical analysis to determine subject, predicate, restriction, condition, causation, and emphasis. Without grammar, interpretation becomes conjecture.

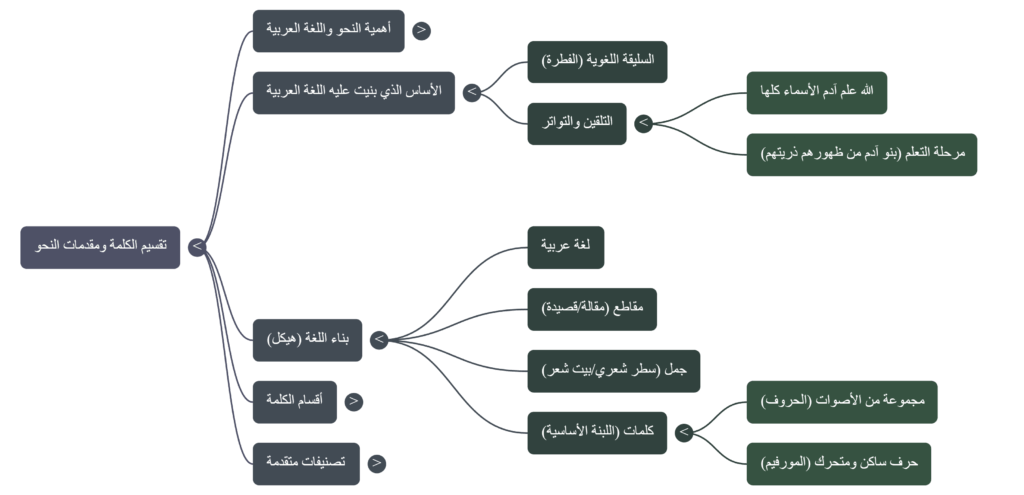

2. Arabic Before Islam: Linguistic Intuition and Transmission

Before codification, Arabic lived in the mouths of its speakers. It was governed by salīqah—linguistic intuition—rather than written rules. Language was transmitted through repetition, memorization, and communal usage. Tradition holds that God taught Adam language, and it passed through generations by oral transmission.

With the expansion of Islam and the entrance of non-Arab speakers, errors (laḥn) emerged. The Qur’an—unchanged, exact—necessitated grammatical codification to preserve meaning. Thus, grammar arose not as an innovation, but as a safeguard.

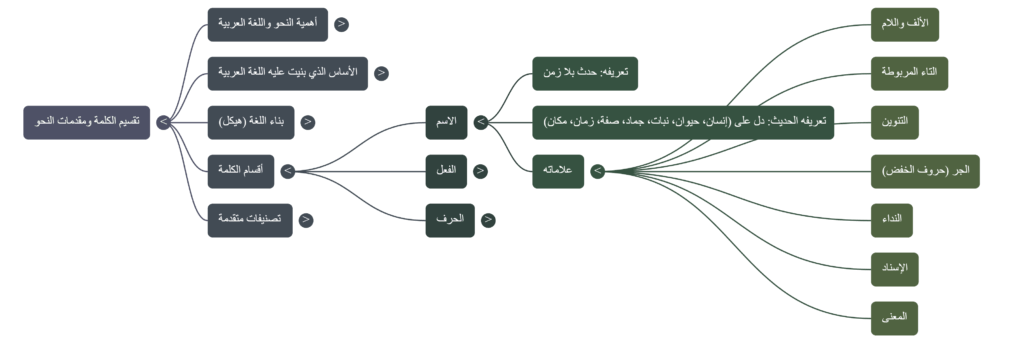

3. The Three Categories of Words: Noun, Verb, Particle

Arabic grammar classifies all words into three foundational categories:

3.1 The Noun (Ism)

A noun signifies a meaning in itself without reference to time. Its grammatical markers include:

- Genitive case (kasrah)

- Tanwīn

- The definite article (al-)

- Vocative particles (yā)

These markers are not decorative; they determine syntactic function and theological implication.

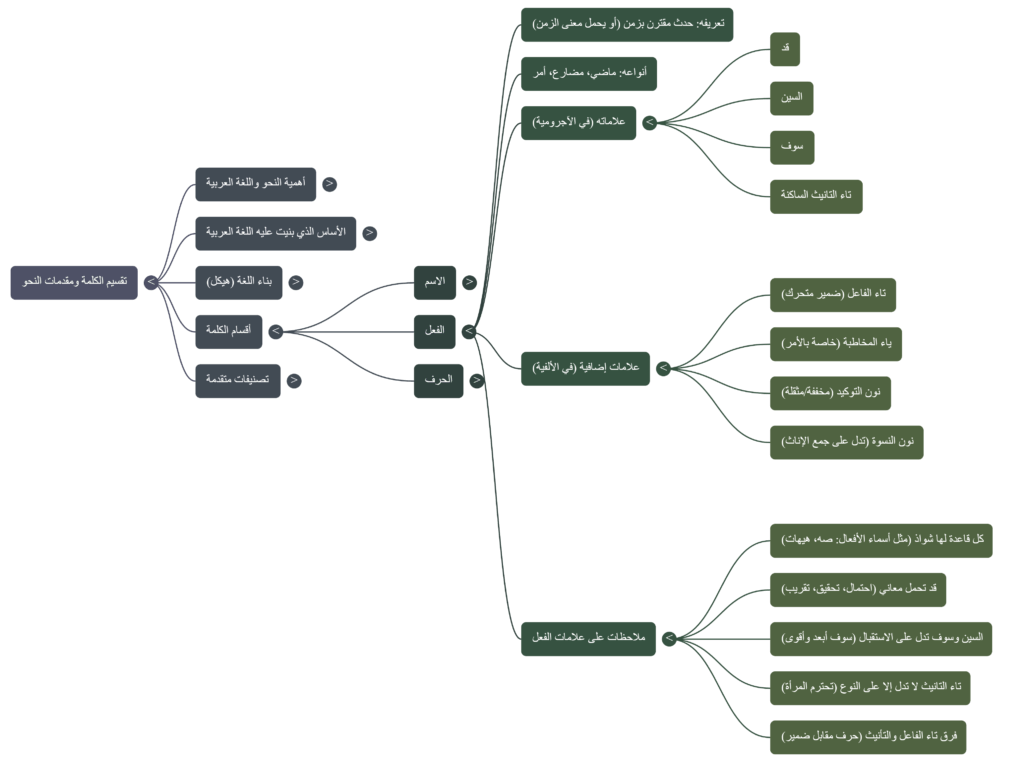

3.2 The Verb (Fiʿl)

A verb signifies an action linked to time:

- Past (māḍī)

- Present/Future (muḍāriʿ)

- Imperative (amr)

Verbal markers signal tense, certainty, emphasis, and agency.

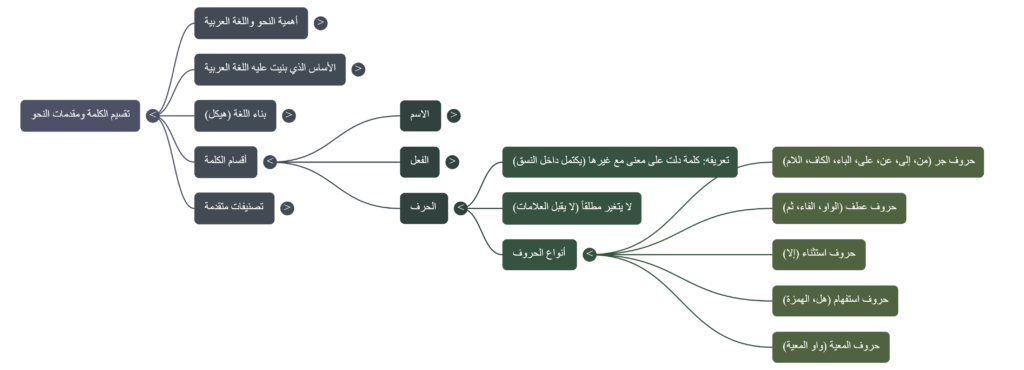

3.3 The Particle (Ḥarf)

A particle conveys meaning only in relation to other words. It is indeclinable and includes:

- Prepositions (min, ilā, ʿan)

- Conjunctions (wa, fa, thumma)

- Interrogatives (hal, hamzah)

Particles quietly govern relationships that reshape meaning.

4. Verbal Markers: Precision Beneath the Surface

The lecture referenced in the source video devotes careful attention to verbal markers:

- Qad (قد):

- With past tense: certainty or verification

- With present tense: possibility or rarity

- Sīn (سـ) and Sawfa (سوف):

Both indicate future tense; sawfa implies a more distant future than sīn. - Feminine Tāʾ (تاء التأنيث الساكنة):

Attached to past verbs to indicate a feminine subject; it has no syntactic position. - Subject Tāʾ (تاء الفاعل):

A pronoun, always vocalized, occupying the grammatical role of subject. - Emphatic Nūn (نون التوكيد):

Exists in heavy and light forms, intensifying certainty.

A single letter, silent or vocalized, may recalibrate meaning entirely.

5. Distinguishing the Two Tāʾs: A Crucial Boundary

Confusion between the two types of tāʾ leads to serious interpretive errors:

- Feminine Tāʾ:

A silent suffix, grammatically neutral, signaling gender only. It holds no syntactic position. - Subject Tāʾ:

A pronoun, grammatically active, functioning as the subject of the verb.

Mistaking one for the other is not a minor lapse—it alters agency and meaning.

6. Types of Particles: Silent Architects of Meaning

Particles are numerous, fixed in form, and decisive in function:

- Prepositions: impose genitive case and semantic relationships.

- Conjunctions: connect clauses, sequence actions, or contrast meanings.

- Interrogatives: transform statements into inquiries, sometimes rhetorical.

Their immobility conceals their power.

7. Grammatical Error and Creed: A Qur’anic Example

A famous example illustrates the danger of grammatical negligence:

“Indeed, Allah is free from the polytheists and His Messenger”

(Qur’an 9:3)

Improper case endings or pauses could imply—incorrectly—that Allah dissociates Himself from His Messenger. Correct grammar clarifies that both Allah and His Messenger are free from the polytheists, not from each other.

Historical reports mention that such an error prompted early scholars to formalize grammar.

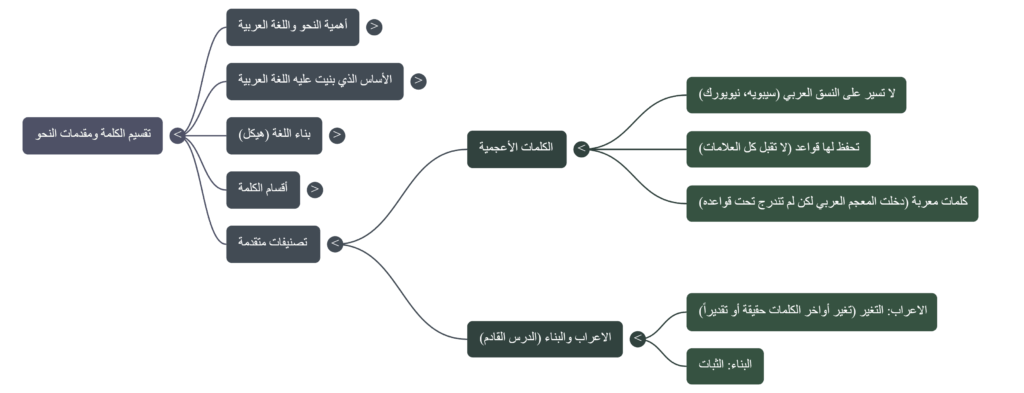

8. Definiteness and Divine Attributes: “Raḥīm” vs. “Al-Raḥīm”

The definite article al- does more than specify—it may imply completeness, exclusivity, or perfection.

- Raḥīm: merciful, as a general attribute

- Al-Raḥīm: the One whose mercy is complete, inherent, and unsurpassed

In theology, such nuances matter. Grammar here guards creed.

9. Linguistic and Juristic Benefits of Mastering Grammar

- Protection from doctrinal distortion

- Precision in legal derivation

- Unveiling Qur’anic eloquence

- Restraint against arbitrary interpretation

Grammar disciplines interpretation before it disciplines language.

10. A Practical Method for Grammatical Qur’anic Reading

- Identify word categories (noun, verb, particle).

- Determine inflectional markers.

- Examine connectors and conjunctions.

- Consider recitational pauses and early readings.

- Integrate grammar with jurisprudence and rhetoric.

Conclusion: Grammar as the Bridge Between Tongue and Revelation

Grammar is neither a cage nor an ornament. It is a bridge—between sound and sense, between recitation and realization. To claim that intuition alone suffices is to underestimate the precision of divine speech.

At quranst.com, we invite the reader to:

- Study grammar as a means, not an end;

- Unite linguistic rigor with spiritual humility;

- Question methodically, for disciplined doubt leads to truer certainty.